The now fully restored neo-classical orangery at Tyntesfield, Wraxall in Somerset is a joy to see, and a very different sight to the one I saw in 2006 when I wrote about it for my Architectural Association dissertation on historic orangeries. Then in a parlous state: weeds sprouting from interior walls; protective roofing; decayed stonework supported by scaffolding

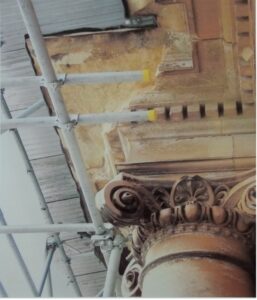

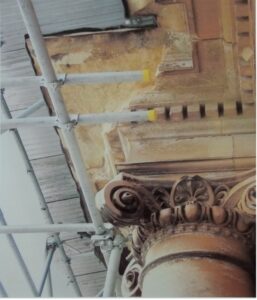

A view of one of the portico capitals. © Helen Langley, 2006.

Commissioned by Antony Gibbs (1841-1907), designed by the now largely-overlooked Arts and Crafts architect and designer, Walter Cave (1863-1939), with youthful exuberance, if perhaps insufficient technical experience to foresee subsequent problems. Tyntesfield was Cave’s first garden, and his third commission from Gibbs who had interests in Devon, Cave’s home county. Gibbs’ two Devon projects, one of which included the monument in Ottery St Mary to mark Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, are mentioned in a article by Judith Patrick published by the Devon Gardens Trust here.

The Tyntesfield scheme was sited in the re-modelled kitchen garden of 1890-1910 and within walking distance from the house, using the then new stone-flagged path. A destination for family and visitors as they circuited the gardens and grounds. An allusion, perhaps, to eighteenth century notions of entertainment.

The 1897 orangery graces the Jubilee Garden its name again referencing Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The complex comprises the Lady Garden (now known as the Lady Wraxall’s garden); loggia, cutting garden, head gardener’s office; rooms for tools and potting, storing apples, and the boiler (the distance of which from the orangery was once thought to have contributed to the latter’s original problems); walled kitchen garden and range of glasshouses. Nearby is a bothy, also by Cave.

From the outset the site was intended to be ‘on display’ – a formalised productive garden with an ornamental role. Large oranges, oleanders and camellias were cultivated in the orangery which also served as an occasional reception room. (The galvanised steel window frames are twentieth century). After the Second World War it became a greenhouse. Back in the early 2000s this Grade 11* building’s future was far from secure; it seemed on the point of collapse. Tyntesfield’s acquisition by the National Trust in 2002 was a game changer. It ushered in plans for restoring the estate. The orangery which had been placed Historic England’s Buildings at Risk list in 2008 was finally rescued in an imaginative collaborative programme with funding by the HLF and the Commercial Education Trust. The latter funded a three-year training course with students from the Architectural Stone Conservation course at City of Bath College. Nimbus Conservation Ltd were the principal contractors.

A detailed account of the project is available here.

On the day of our visit in May 2024 the orangery was a glorious sight; the scent of the citrus trees delicious.

A view across the cutting garden. © Helen Langley, 2024

Many years ago, when writing about political houses and gardens, I was given access to two of Cave’s later schemes, both in Oxfordshire; The ‘neo-William and Mary’ Wharf (then divided into two properties) in Sutton Courtenay and the exterior and gardens of the Tudor style Ewelme Manor. c.1910. The Wharf was of particular interest because it had been commissioned in 1912 by the Prime Minister’s wife, Margot Asquith, later Countess of Oxford and Asquith (1864-1945), in the forlorn hope of improving the amount of quiet time spent with her husband (sadly for her it’s where Asquith wrote many of his love letters to Venetia Stanley, later Montagu (1887-1948). The detailing at Tyntesfield, especially the Lady Garden, loggia and the head gardener’s office, is reminiscent of both Ewelme’s and High Walls in Headington Oxford, c. 1912.